Nationalist troops in a trench, Dadaos at the ready. Photo was probably taken sometime in the 1930s.

Rediscovering the Dadao: A Forgotten Legacy of the Chinese Martial Arts.

Any review of the history of the Chinese martial arts in the 20th century will quickly suggest that these civilian art forms have, at various points, been co-opted and used to advance the aims of the state. Both the Nationalist (GMD) “Guoshu” program and the later Communist (CCP) “Wushu” movement sought to use the martial arts to strengthen the people, improve public health and build a sense of nationalism. However, these movements have also had a darker side. In times of conflict both national and local leaders have used them to militarize the population, supporting paramilitary organizations and guerrilla forces. These activities were widespread during both Second Sino-Japanese War (WWII from an American perspective) and the long running Chinese Civil War. Some martial arts schools, such as the Foshan Hung Sing Association (which was closely aligned with the CCP during the 1920s and 1930s) continue to promote and glorify these stories today.

Nowhere is the association between the martial arts and the militarization of the population more evident than in the creation of “Dadao Teams” between the 1920s and the 1940s. Receiving a contract to train one of these organizations on behalf of a political party, or other organization, was a major source of pride and an important form of economic patronage for civilian martial artists. In southern China (my own geographic area of expertise) leaders in the Hung Gar, Choy Li Fut and Pakmei styles (among others) were all actively engaged in training of citizen militias which were subsequently embroiled in a number of conflicts.

It goes without saying that a truly effective militia would have to be armed with modern rifles. However, the weapon that most captured the public’s imagination, becoming the defacto symbol of the paramilitary organization during this period, was the Dadao. This blade caught the mood of the country for many reasons. It harkened back to a romanticized view of the past, and it advertised the “martial skill” and attainment of the one who could wield it. It was a visually impressive weapon and had a long association with the less pleasant aspects of Chinese law enforcement. In fact, the Dadao was often an implement of terror.

This is the critical aspect of this weapon that is so often overlooked by modern martial artists with romantic notions about the past. Individuals often wonder why Chinese troops were issued a cumbersome bladed weapon as late as the 1930s. Surely this would be ineffective against Japanese machine guns and artillery?

China’s military officers were often poorly equipped and stretched to the limit, but they were not stupid. They realized that the Dadao would have limited value on the modern battlefield. Yet much of China’s brutal civil war revolved around capturing, controlling and projecting authority into villages and urban areas. The Dadao proved to be an effective means of producing terror, and therefore compliance, within the civilian population.

The weapon had another advantage as well. It could be produced very cheaply in almost any small shop or forge in the country. China was certainly capable of producing modern weapons (though admittedly their quality was variable). But it was still cheaper to arm the home guards, militias and second line troops with traditional weapons such as the spear and the Dadao. These troops often receive the rudimentary training they needed from local martial artists, and while they were not effective on the battlefield, they could be a useful resource when it came to the more mundane tasks of maintaining order and dealing with traitors. It was these two factors, the cheapness of the Dadao as a second line weapon, and the terror that it inspired as a tool of public control, that ensured the weapon’s survival well into the mid-20th century.

Currently the Dadao is enjoying something of a revival among students of the Chinese martial artis. The growing sense of nationalism within mainland China, and increased curiosity about history in the West, are conspiring to bring the Dadao back into the training hall after a nearly half century absence. The recent uptick in the popularity of “realistic” weapons training also seems to be accelerating this general trend. Further, it was so popular in the 1920s and 1930s that there are many different styles of use just waiting to be “discovered” and reconstructed.

Both practical and historical students of the Chinese martial arts might benefit from a brief description of these weapons as they actually existed and were used from the closing years of the Qing dynasty through the end of WWII. We are also fortunate in that this period is extensively documented. This provides us with the sorts of photographs and accounts that students of earlier periods of martial history can only wish for. All of this makes the sudden rise and fall of the Dadao a good case study for change and adaptation within the Chinese martial arts more generally.

One could easily write a book on the Dadao and what it reveals about the evolution of the Chinese martial arts and their ever evolving relationship with society. Clearly such a project is beyond the scope of this article. Instead I hope to use a number of historically important pictures to suggest the basic outline of this story. A more comprehensive treatment will have to wait for a later date.

However, there are number of outstanding issues that must be addressed before we can undertake even a brief review. First, there is little consensus as to how to best translate “Dadao” into English. The character used for “Da” means “big” or “large.” “Dao” translates to “single edged knife.” Unfortunately “Dao” does not imply anything about the length of the knife in question or its intended purpose. A paring knife or a cavalry saber can both be referred to with this same term in Chinese.

This causes confusion when students of the Chinese martial arts speak in English with non-specialists. They are often adamant that a Chinese military saber should be called a “knife”, which is technically correct in Chinese, but is absurd in English. A literal translation for Dadao would be “big knife.” Yet when talking about a weapon that might be three feet long and requires two hands to wield, such a rendering seems calculated to cause confusion.

Some martial arts teachers refer to the Dadao as the “military machete.” While this does not attempt to be an exact translation of anything it does provide the reader with a basic visual image of what is being discussed. The broad blade of the Dadao does (to some degree) resemble the short broad blade of a jungle machete. It is also the sort of tool that one might expect military troops to carry.

Still, there are problems with this translation. It implies that the Dadao might be a tool with some sort of practical application. I suspect that this is mistaken. I have never run across an account that indicates that these weapons were useful “camp tools” in the same way that a kukri or a machete might be. The Dadao is a purpose-built chopper. The blade of the machete is thin and flat to cut vegetation without resistance. Most Dadaos have a much heavier blade with a triangular profile. They are really only good for hacking through flesh and bone. The heft of the weapon is distinctively ax-like.

For all of these reasons I favor translating Dadao as the “military big-saber.” This should be enough to convey that we are dealing with a single edged weapon that differs from other, more conventional sabers. It also has the added advantage of being a somewhat popular solution to our linguistic quandary.

Our second problem has to do with the photos below. I gathered most of these off the internet and while I have spent a couple of hours trying to figure out where they were originally published, that has not always been possible. The circular republication of vintage material with no attribution of its ultimate origin is a problem in a lot of the Chinese language literature on the martial arts. If any reader has firm information about the origins of an unlabeled photo, please let me know in the comments. I am currently trying to collect this information.

Origins of the Dadao

Our first puzzle has to do with the early development and adoption of the Dadao. While 20th century examples of these weapons are quite common, very few examples can be reliably dated to the early Qing dynasty. This is odd as Qing military regulations dictated that a number of these swords should be issued to every unit, but evidently they did not survive in great numbers. Occasionally weapons turn up on the antique market with very early dates or are even attributed to the “Ming era.” Great caution is required as few swords from the Ming period have survived at all and I don’t think I have ever seen a Military Big-Saber that dates to this period.

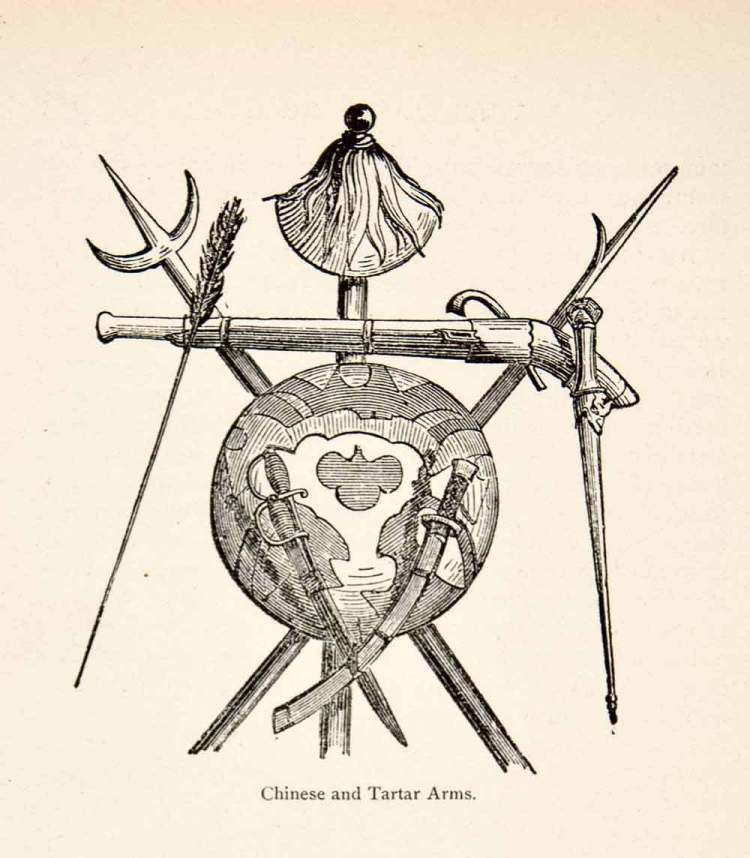

Still, one school of thought basically holds that the modern 20th century Dadao is a resurrection, or a re-imagination, of a classic Ming era weapon. While similar weapons seem to have become less fashionable during the early Qing (though regulations did exist for its use in the army), stories of the Ming dynasty and the exploits of its heroes became quite popular in the 19th century. When republished these stories were often illustrated with copies of Ming era illustrations, or with new images of heroes dressed in Ming style cloths with antique weapons. Their swords often featured ring shaped pommels and clip point blades. In fact, many of the same fashion styles were preserved in both Mandarin and Cantonese theater companies so people were fairly familiar with them.

A Ming era publication that shows images of Dadao like swords. Images of these swords were probably popular in period publications because of their dramatic blades.

The end result of all of this is that the image and the lore of the Dadao was easily available for anyone seeking to resurrect the glory days of China’s martial past. It was occasionally seen in the official military, and it was often featured in stories and popular fiction. Further, the simple blade and ring pommel design would have been fairly easy to produce compared to the more complex dao’s of the mid-Qing. Such swords were often favored by the various “Big Sword” militia groups that became increasingly common from the end to the Taiping Rebellion onward. The arms of these groups carried romantic associations with the past and often included the ringed pommels. However, they featured a wide variety of blade types from long sabers to short heavy choppers. While the idea of the “Big Sword” was a common symbol in 19th peasant militias, I haven’t seen much evidence to indicate that they standardized on any one weapon in particular.

A second theory is that the modern Dadao actually has little to do with its ancient predecessors or weapons used by the Imperial military. There is at least some evidence to support the assertion that a Dadao is basically an enlarged and modified farm tool. This would hardly be the first time that a farm implement found its way onto the battlefield. The Nepalese kukri was an agricultural tool long before it was used by the British Gurkha’s in WWI. It might also help to explain why Chinese smiths often made the blades of the Dadao shorter than one might expect for a weapon. They may have had some other pattern in mind when doing their work.

If you look at antique farm implements, or even wander around a traditional food market in Hong Kong or Shanghai, you will see lots of chopping knives that look like scaled down versions of a Dadao. Often these seem to be favored by vendors selling tough skinned fruits or vegetables. Butchers simply use the traditional cleaver. Still, while similar in shape and function, there is a world of difference between the Dadao and a “watermelon knife.”

A third suggestion that I have seen offered is that the Qing era civilian Dadao is really a modified pole weapon. The Chinese military traditionally employed a number of pole-mounted choppers, and the blades of these weapons resemble the basic size and profile of a Dadao. The type of riveted handle seen on many Dadaos is also very similar to the long riveted tang that is preferred in the construction of large heavy choppers. The handles of normal sabers or “Daos” are peaned in place, rather than riveted.

This theory may have something to it. In antique auctions I have personally seen Dadaos constructed from much older pole mounted choppers whose shafts had been lost or broken. This sort of recycling was pretty common on the “Rivers and Lakes” of China. Further, for reasons that we will explore below, there are no standard measurements for what a “regulation” Dadao must be. This is not say that various self-appointed experts did not have opinions on the matter. They certainly did. Yet seems that few manufactures were actually listening all that closely. For instance, some examples being made up through the mid 20th century continued to have very long handles. It is not always clear whether a given weapon should be classified as a Dadao (Military Big-Saber) or Pudao (Horse Cutting Knife).

At the moment I do not feel that there is enough evidence to speak decisively on the evolution of the Dadao and its subsequent adoption by civilian martial artists. What we do know is that the coming of the Qing Imperial army privileged the conventional saber as it could be used from horseback whereas the two handed Dadao is strictly an infantry weapon. While the heavy chopper seems to have faded from public consciousness it never totally disappeared and it’s popularity among civilian martial artists, bandits, guards and paramilitary organizations exploded during the final decades of the 19th century. This resurgence in popularity was further boosted in the 1920s and 1930s.

These groups were likely attracted to the Dadao for three reasons. First it provided a visual connection to the romanticized Ming dynasty. Second, it was a simple weapon that could be produced practically anywhere. Lastly, being a double handed weapon individuals who had grown up using farm tools (and that was pretty much everyone in China) could master it relatively quickly. What it lacked in range or sophistication it made up for with its immense slashing and chopping power.

The Dadao as an Instrument of Police Control in Late Imperial and Republican China.

Modern researchers and collectors are fortunate in that we have copies of the official regulations governing weapons bought by the Qing government for the imperial armies.

While the single handed saber was clearly the preferred weapon, enough period choppers survive to attest their use in the Qing army. These weapons came in two official varieties. The “kuanren dadao” is a very large weapon, more on the scale of a horse knife. The Qing-era “chuanweidao” is smaller and shows more similarities to the modern Dadao.

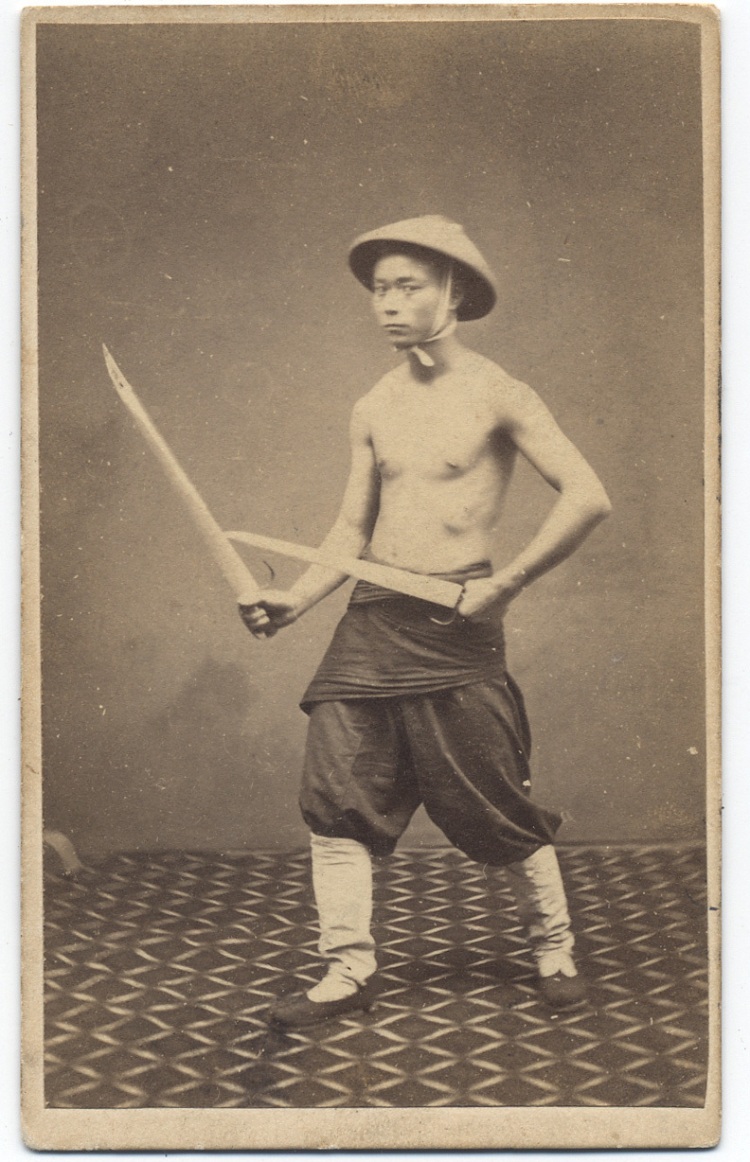

Period photographs give us a good visual record of how these swords were actually being used by the end of the Qing dynasty. Not many photos of Qing era troops armed with any sort of sword at all survive from the final decades of the dynasty. From the end of the Taiping rebellion on, all main-line Qing troops had modern rifles. By the time of the Boxer Uprising they also had modern machine guns and artillery. Officers continued to carry swords, but increasingly even these followed European patterns.

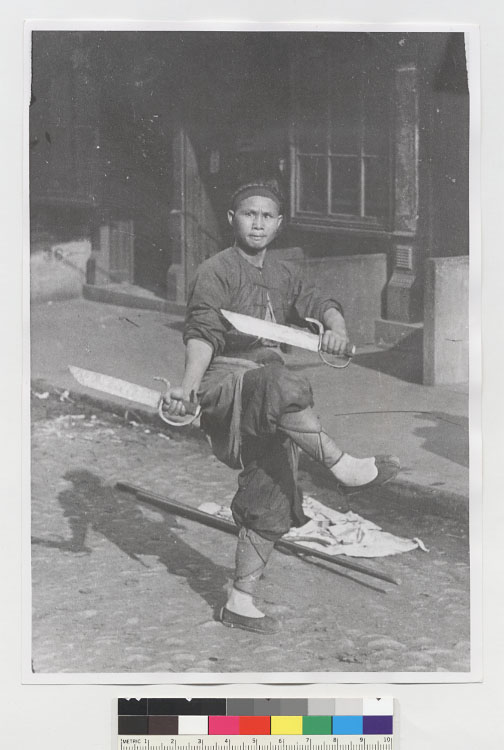

The one place where the Dadao really seems to have survived was in law enforcement. Specifically, public executions and beheadings were often carried out with the dadao or some sort of similar, often very short, chopping blade.

The picture below records two executioners displaying their weapons prior to the public beheading of the perpetrators of the 1895 “Kucheng Massacre.” This is an important photo for a number of reasons. To begin with it has a clear provenance and is linked to specific, date, place and historical incident.

The weapons being displayed are also quite interesting. The gentleman on the left has what appears to be a fine Japanese Tachi. Note that the flash from the camera has illuminated a section of active hamon at the base of the blade. One can only wonder how this sword ended up in the arsenal of the local yamen. It is a good reminder that the Chinese have been very interested in Japanese swords since at least the Ming.

The other executioner carries a short, heavy bladed chopper. It has a simple guard and the handle, almost as long as the blade, is wrapped in cotton cloth (probably colored red). The blade looks too small for its intended task, yet execution swords were often not much longer than this.

An executioner displaying a pile of heads along with his weapon. Note that the sword is a short heavy “jian” (double edged sword) rather than a Dadao. It should be remembered that executions were carried out with a variety of tools. Very often these are shorter than one would expect, but apparently that did not impede their efficiency. This particular photo probably dates to the 1920s and was published on period ephemera. It can sometimes be found on vintage postcards and stereoscope slides.

The Dadao was also seen in urban police and law enforcement units. Chinese governments worked hard to establish modern law enforcement in the major urban areas between 1900 and 1930. Some of these reform efforts drew on western ideas of “scientific” criminology and law enforcement, others did not. Very often 3-4 different types of law enforcement might be operating in a major city at one time. For instance, there might be a model western style police force under the control of one office, a group of plain cloths detectives (who were expected to be close to, or even part of, the criminal underground) who answered to a different office and lastly there were usually patrols of military police to maintain “public order” in the street. In cities such as Shanghai the situation could be even more complex.

A Qing era police patrol. Note the mix of both modern rifles and a Dadao, used for executions. This photo was a popular subject for reproduction and can sometimes be found on vintage postcards.

For much of the early 20th century it was the “military police” that one would most likely see in public spaces. Under both the Qing and Republic governments these individuals were normally regular infantry soldiers who were assigned to the task. Often soldiers from a different part of China were chosen to be law enforcement officers as it was thought (usually incorrectly) that linguistic difficulties and regional animosities would make them less susceptible to local corruption.

These police officers would generally travel in small groups of between 4-6 individuals. They might include an officer or a Sargent who acted as the leader, 2-3 individuals who could apprehend criminals, and an executioner. Individuals who were caught stealing or causing disorder in the market place would be apprehended, bound and usually beheaded in the middle of the street after a very brief “trial.”

It is important to realize that early 20th century China was a highly volatile place. The government, whether run by the Qing, the Republic or individual Warlords, attempted to keep the population in check through what amounted to a continuing campaign of public terror. This is how the Dadao was first seen by most of China’s citizens. It was the living embodiment of the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence.

Dadaos in the Republic of China and Warlord armies of the 1920s-1930s.

One cannot underestimate how strong these symbols are or how deeply engrained they become in the public psyche. The situation in China was complicated by the fact that large parts of the nation’s leadership and population did not agree on who held actual political authority and the rights to exercise public violence that went with it. As a result Nationalist (GMD) revolutionaries were quick to adopt the Dadao as a tool of public law and order after they succeeded the Qing. They too employed military police and the display of the Dadao left the public in no doubt as to who could claim rightful control of the state.

An early image of an unknown group of soldiers, all armed with very long handled Dadaos. Probably 1920s.

Nor were they the only group to realize the political utility in the Dadao. Bandit gangs and armies in the central plains and western China had long valued the Dadao for its more practical attributes. As these gangs were gathered into the various “Warlord Armies” they took the Dadao with them. Even though they were now armed with rifles, handguns and grenades, the Dadao remained a powerful symbol of both the personal and corporate “will to power.”

Member of a northern Warlord Army displays his Mauser handgun and Dadao. This picture probably dates to the 1920s.

A commonly republished photo showing nationalist soldiers in ranks all carrying Dadaos. Date unknown, probably 1930s.

It is worth remembering that a variety of blades were carried by Chinese troops between 1920 and 1945. Not even all “Big Sword” units were issued Dadao. This photograph shows the 8th March Army displaying a different style of double handed saber in 1933.

It was the soldiers of these western armies that would bring the Dadao to the attention of the wider world through their desperate attempts to defend the Great Wall against Japanese advances in 1933, and then the “Marco Pillar Bridge Incident” where they defeated a superior Japanese force using a Dadao charge in 1937. In their hands the Dadao became a dual symbol to the outside world. It represented the fact that the Chinese people were willing to fight for their own freedom (something that was often doubted in the West), but it also encapsulated and reinforced nearly a century’s worth of fears and prejudices. The personal nature of this weapon seemed to suggest that the Chinese reveled in violence and brutality, and were still “less than civilized.” In China public executions and the Dadao acted as a twin symbolic code for “political authority” and “legitimacy.” Unfortunately these symbols did not translate well in the more liberal west.

An American trading card from the 1938 “Horrors of War” series. This image was labeled “Chinese ‘Big Sword’ Corps Resist the Japanese.” Author’s personal collection.

The domestic situation in China was different. If anything the importance of the Dadao as both a practical and symbolic weapon increased as the 1920s turned to the 1930s. After the rupture with the Nationalist Party (GMD), and the subsequent outbreak of violence with the Japanese, the CCP began to form larger militia units. These groups were expected to both fight the GMD and the Japanese, as well as to pacify and hold segments of the country side. Once again, the Dadao was a featured weapon in their arsenal.

Other paramilitary groups, such as railway police units, were also quick to adopt the Dadao during this period. As a matter of fact, it is among these other troops that the Dadao is most commonly encountered. I have looked through enough photos of military units during the Republic of China period to conclude that the Dadao was actually rarely encountered among front-line infantry troops. While there certainly were “Big Sword Teams” within the main body of the Nationalist Army, they were an exception rather than the rule. Most often such swords are seen in the hands of special forces troops, military police, local militia, paramilitary revolutionaries and railway guards. All of these groups were more likely to deal with the domestic population than the Japanese.

One of the most famous images of a Chinese soldier with a Dadao. Originally published as a postcard, the individual in this image is actually a railway guard.

The Dadao as a Paramilitary and Militia Weapon

Selection bias is an issue that every military historian must confront. There are a handful of photographs and historical accounts of the Dadao’s use by Republic of China (ROC) troops which have had a disproportionate impact on how we imagine the weapon in the west today. In reality most troops in the various ROC armies were not organized into “Big Sword Teams” and we are still talking about the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident” because such events are so rare. In fact, the story of this supposed triumph is really a very sad tale. If the Chinese troops had been better armed, reinforced and had more ammunition they would not have been forced to close with the Japanese and engage them with swords and bayonets in the first place. It is hard to imagine that there were really any commanders in the war hardened Chinese army of the 1930s or 1940s that actually wanted to engage the enemy with a sword charge.

Militia and paramilitary groups were in a different situation. These were basically local support troops. Their job was usually to secure rear areas and maintain order in the countryside. They were not expected to act as front-line troops. As we have already seen, the Dadao had a long and respected relationship with “law and order.” While the modern collectors like to focus on the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident,” the actual truth is that these swords were much more likely to be used in the commission of “police actions” or (war crimes, depending on one’s perspective) than anything else. For that purpose they proved quite effective.

They were also favored by militias for a number of other reasons. While Mauser rifles were cheap enough that warlord armies and criminal gangs could buy them by the crate, the same could not be said of local militia. These small groups were often comprised of struggling farmers just trying to get enough to eat and feed their families. Modern rifles and large stocks of ammunition were often not an option for militia groups.

Members of a local militia outside of Guangzhou assembling in the summer of 1938. Note the mix of modern and traditional weapons. The Dadao can be seen leaning against the tree. Photo by Robert Cappa.

As a result, both spears and Dadaos tended to be frequently seen in peasant groups and revolutionary societies. These weapons could be quickly produced by any local smith, and they often helped to augment the few modern rifles that were laying around the village. In this sort of landscape the Dadao was still a very effective weapon. The Dadao also had a certain cache in peasant circles as it harkened back to the “Big-Sword” militias of the 19th century and the vast body of folklore that surrounds them.

Swords were also favored by the martial arts teachers who often served as instructors of militia groups or other civilian paramilitary organizations. Most Chinese martial arts had sword forms in their repertoire and these could be simplified to fit the Dadao. Further, as a two handed chopping weapon it was not totally unfamiliar to the peasant troops who were asked to use it.

In southern China Cheung Lai Chuen, the founder of Pakmei (White Eyebrow) gained local fame by training a civilian “Big Sword Team” at the local Guoshu Institute in Guangdong during the 1930s. Of course Cheung was closely allied with the GMD. The leaders of the Foshan Hung Sing Association (formally closed by the Nationalists in 1927) returned to the area from Hong Kong in the late 1930s to train a Communist militia force.

If anything the Dadao was even more popular with martial artists in the north. In 1933 Yin Yu Zhan (an important Bagua teacher, his name is also rendered Jin En-Zhong) published a manual titled Slashing Saber Practice (Shi yong Da Dao Shu). This work is interesting because it not only discusses practical techniques for using the Dadao that may date to the late 19th century, but because the author takes the time to briefly discuss the role of the Dadao in recent Chinese military history. He notes a number of battles in the first Sino-Japanese war (1894-1895) in which this weapon was used effectively, and claims that when properly understood it still had a place on China’s modern battlefield.

Yin Yu Zhan. Illustration from Slashing Saber Practice, 1933. Kennedy and Guo provide a detailed discussion of his publications in their volume, Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals, 2005. According to Yin Yu Zhan the ideal Dadao is 35 inches long and 3.5 pounds.

In the hands of teachers like Cheung Lai Chuen and Yin Yu Zhan the image of the Dadao was transformed once again. More specifically, it was democratized. What had once been a sign of state authority was devolved to the individual citizen who, through training and hard work, could now “defend the nation.”

For martial artists the Dadao and the bayonet became very visible symbols of the place of traditional hand combat in the modern world. They were concrete reminders that could be pointed to every time the “May 4th Reformers” began to complain about how there was no place for an activity as “backwards” and “superstitious” as boxing in modern China. Not only could the martial arts still exist, they were desperately needed by both the state and local government as they attempted to raise militias and paramilitary groups.

William Acevedo was kind enough to send me a copy of this picture where the banner being held in the foreground is now legible. Thanks so much! “Guangdong Province Women Teachers sends the 29th Army relief goods.” Thanks goes to my brother Sam in HK for a quick translation.

Members of an all-female militia armed with Dadaos. I am currently looking for any information about the date or origin of this photo. Please contact me if you know where the original was published.

This democratization of violence extended beyond just weaponry. During the 1920s women started to make great strides towards equality in modern Chinese life. Nowhere was this more evident than in the Jingwu Society, a national martial arts organization from Shanghai that accepted female members on equal terms. The later state sponsored Guoshu movement also promoted female martial artists, though more grudgingly.

In the 1930s all female militia groups and paramilitary auxiliaries were created. These women often received some rudimentary training and were occasionally armed with the venerable Dadao. It was not practical to arm them with rifles, and machine pistols were often too valuable. For auxiliary organizations serving in rear areas, the Dadao once again proved to be the perfect weapon.

It is also interesting to note how seriously many of these women took their training and arms. Many decades after the end of hostilities, civilian descendants of some of these original militia groups still practice with the Dadao in Taiwan. This is a fascinating artifact of the weapon’s rich association with Chinese life in the mid-20th century.

Women holding Dadaos. William Acevedo has informed me that they may have raised the money to pay for a shipment of weapons are are posing with some of the swords in the above picture prior to their donation. If anyone else has more information of this photo (or a better copy of it) I would like to hear from you.

Here are the same four women with officers from the 29th army. Note the soldier in the left side of the picture holding a Dadao at attention. Source: William Acevedo. This photo is part of the memorial at Xifengkou, ca. 1933.

Collecting Antique and Vintage Dadaos

The last section of this article addresses the Dadao as a physical object. As a general rule antique Chinese swords are difficult to collect. Authentic examples are rarely exported from China (which strictly controls the trade in antiques) and the few that are for sale in the west often sell for thousands of dollars. Many of the swords that are for sale out of China are either partial or complete fakes. While other countries may have a “cottage industry” in the production of doctored weaponry, the Chinese antique market mass produces fakes on an almost mind-boggling scale. If you go to eBay and type in “antique Chinese sword” almost everything you see from China (maybe 98%) will be a fake.

As a result, most students of Chinese martial studies and the Chinese martial arts have never actually held a genuine example of the weapons that they write about or train to use. This is a less than satisfactory situation. I strongly believe that a familiarity with actual historic weapons is a needed antidote to many of the myths that are commonly circulated in both historic and practical circles.

Dadaos are interesting in this regard as they occasionally appear on the antique market at reasonable prices. They are not antiques and can be exported from China. Hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of these weapons were made during the 20th century, making them quite a bit more common than Qing-era regulation sabers.

Fakes, often of poor quality, are still a problem. This is ironic as occasionally one can buy an authentic Dadao for less than a fake copy. If you are thinking about buying a Dadao do your research. Visit electronic forums with a community of experienced collectors and familiarize yourself with vendors who sell legitimate artifacts. And remember, everyone in the collecting world gets burned at least once.

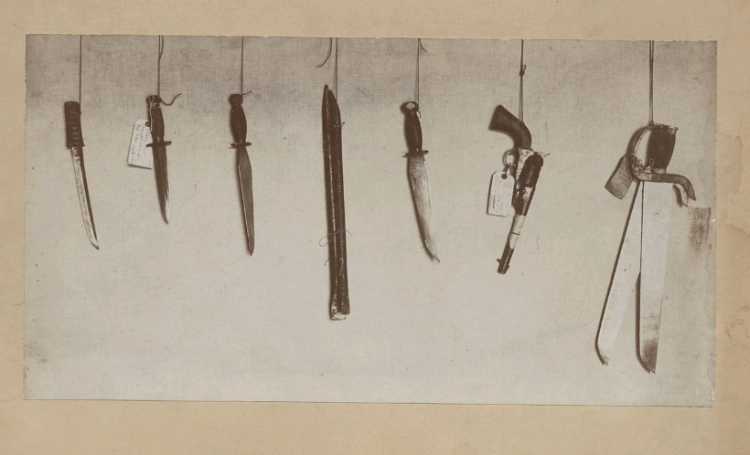

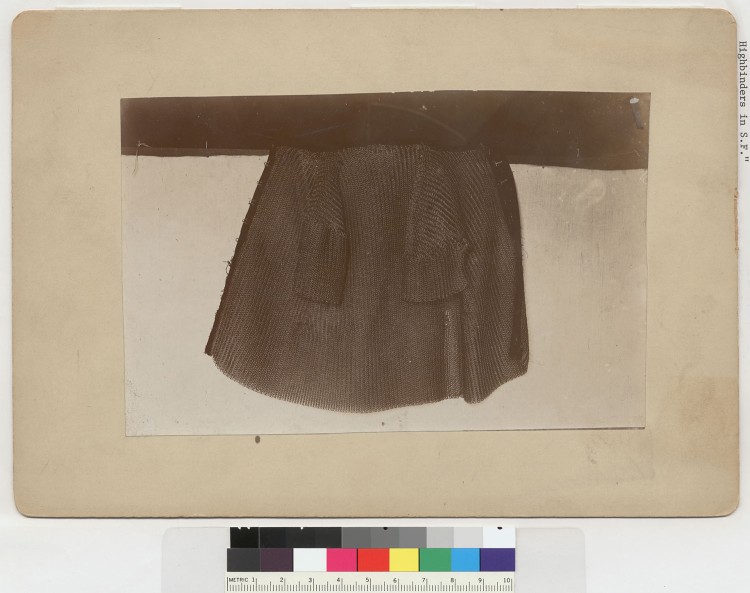

Pictured above are two examples of Military Big-Sabers from my own collection. One of these swords was bought from an antique dealer in the US and the other from a trusted source in China. It is evident from the degree of corrosion on the blades that both date back to at least the mid-20th century, but it is impossible to say too much more. So many different swords were made by so many different shops that it is nearly impossible to guess at the origin of a blade from its style.

While almost identical in length this pair of swords nicely illustrates the immense variability that one sees in the military Dadao.

Top

- Total Length: 79 cm

- Blade Length: 53 cm

- Handle: 20 cm

- Blade Depth: 7 cm

- Width at Spine: 7 mm

- Weight: 1210 grams

- Point of Balance: 20 cm ahead of the base of the blade.

Bottom

- Total Length: 79 cm

- Blade Length: 56 cm

- Handle: 16 cm

- Blade Depth: 6 cm

- Width at Spine: 7 mm

- Weight: 938 grams

- Point of Balance: 14 cm ahead of the base of the blade.

Both blades are identical in length, but the similarities end there. The top Dadao is a heavy chopper. The blade has a thick spine that does not taper as it approaches the tip. The blade also has a simple straight ground v-shaped profile. As a result the weapon feels heavy in the hands and it wants to fall forward when swung. It takes two hands to wield this Dadao, which feels as much like an ax as anything else.

At one point in time the weapon probably had a simple sheet-metal guard which has since been damaged and removed. Likewise it would have been issued with a wood handle held in place with two rivets. The handle slabs have subsequently rotted away, which is common on vintage Dadaos (examples with good condition handles are rare and command a premium). When new the hilt was likely wrapped with a cotton cord to improve the grip.

The bottom sword is a much more refined weapon. While the same length it weighs less and is better balanced. The blade is longer than the preceding example, but the width of the spine tapers dramatically after the first half of the blade. This is a standard sword forging technique and it greatly improves the feel of the blade. The blade is also slightly narrower and can easily be used with a single hand. In fact, that is what any skilled swordsman would prefer to do. However, the handle is still long enough to get a second hand on it for difficult cuts.

Some modern sources go to great lengths to disparage the quality of the Dadao. The Nationalist Party did have trouble producing quality weapons, and the Communists gorillas forces were basically forced to use whatever they could get. It would appear that this general reputation for shoddy construction has worn off on the Dadao as well.

Kennedy and Guo, in an otherwise good article on the Dadao in the Republic of China Army, characterize the physical construction of the Dadao as being too short, too light and too shoddy to strike fear into the heart of an enemy (“Bridges and Big Knives.” In Classical Fighting Arts Vol. 2 No. 14. pp. 55-60). I have studied the Dadao for a number of years now and have handled dozens of examples, and I must say that I respectfully disagree with their overall assessment of this weapon.

“Chinese armies and railway men tore up their railways to prevent the Japanese from using them. Then the railway men carried away the steel rails and girders and welded them into big swords for soldiers and guerrillas to fight the enemy. This is a Chinese railway worker, member of a group of 60 railway workers who banded together to form a cooperative. They use blacksmith forges and bellows to melt and weld the steel rails, then hammer them into swords for use against the enemy.”

Late 1930s

Photographer: Agnes Smedley

Agnes Smedley Collection

Volume 38, MSS 122

While nowhere near the quality of a fine Katana, the average Dadao is very study. Most of them appear to have been made to same standard as a robust piece of farming equipment. That is not much of a surprise when you think about where most of these things were actually made or who used them.

Like any other tool, the Dadao was expected to be used in the field, day after day, and not break. If that is your measure of “quality,” then the Dadao does quite well. Especially when we remember that the Katana is a delicate weapon that requires a finely trained hand. During WWII they did fail under battle field conditions, rather frequently. While not elegant, the Dadao is clearly the more robust weapon. When supplying a peasant army that toughness counts for a lot.

It is certainly true that some non heat-treated Dadaos, cut directly from thin sheet steel, exist. Some have even ended up in museums (one of which was photographed by Kennedy and Guo). In my experience these are the exception rather than the rule. In fact, I suspect that many of these lighter weapons were actually produced for martial artists in the 1950s and 1960s when there was a general move towards more flexible, low quality blades.

The average Dadao from the 1920s-1940s had a heavy blade with a V-shaped profile that descends from a thick spine. The body of the blade is usually mono-steel, though finely laminated examples do turn up. I suspect that they are not more common only because no one bothers to polish and etch these swords.

Almost all period Dadaos that I have encountered have a high carbon steel edge inserted into the blade during the forging process and are differentially heat treated. This may seem like an unexpected luxury on such a utilitarian object, but it was actually the standard way that all knives, and even scissors, were being produced in China by the 1930s. That same very basic technology seems to have applied to the Dadao as well.

Clearly not everyone who produced Dadao’s was a trained blade-smith. I rather suspect that most of these weapons were made by blacksmiths or in local machine shops. As a result, some examples (like the one on top) lack details that you would expect to see on a sword blade. Still, for a two handed chopper what they produced was more than sufficient. If anything the top blade in the photo above is over-built. It appears to embody the same construction ethos as an armored tank. The weapon on the bottom is much more refined and it was probably made by someone who understood the art of sword construction.

Genuine Dadao’s are rarely elegant weapons. Their proportions are never perfect, and many look as though they were carved from a block of steel with a dull chisel. They came in many shapes and sizes. Some had wood handles, others were bound only in cloth. Most were issued without scabbards and were slung across the back with a length of cord. A few others had nicely constructed leather coverings. Many were issued in dull colors, but some sported eye-catching red handle wraps and flowing scarves. All of this reflects the wide assortment of regular and paramilitary forces that employed these weapons for almost half a century. This variety is one of the things that makes the Dadao such an interesting subject of study.

Modern martial artists may be more interested in the high quality reproductions of these weapons that are currently for sale. Hanwei, Cold Steel and Kris Cutlery (among others) all offer their own versions of the Dadao that no doubt surpass the originals in terms of quality control and steel strength. These blades, rather than vintage examples, should be the first choice for anyone interested in doing cutting or forms practice with a realistically weight weapon. Obviously caution, common sense and formal training are the key to doing either activity safely.

Lastly, if you are interested in learning more about historical Dadao techniques, Yin Yu Zhan’s 1933 manual has been translated and republished by a group of historical fighting enthusiasts in Singapore. You can find it here.

While only one example of the sorts of techniques that were popular in the 1930s, I think that this project serves as a model for future research. Hopefully students of other styles will investigate and revive their own 20thcentury Dadao fighting styles. This weapon still has much to teach us about the modern history of the Chinese martial arts.

Conclusion: The Dadao and the Creation of Citizen Soldiers in 20th Century China

The Dadao is one of the most iconic images to emerge from China during the first half of the 20th century. It is strongly associated with the ideas of both “resistance” and “social order.” It became a favorite weapon of martial artists, elite troops and local paramilitary organizations. Far from being an anachronism, it actually seems to have embodied the spirit of the age. Artists, poets and propagandists all found meaning in this simple weapon.

That meaning was not static. It changed and evolved. Civilian martial artists played a critical role in this process. At the end of the Qing dynasty, the Dadao was a somewhat obscure infantry weapon in a rapidly modernizing army. In the hands of law enforcement officers it became an instrument of “official terror” and a reminder of where authority and legitimacy in China’s rapidly changing landscape actually resided. In this setting the Dadao represented the claims of centralized authority. As a constantly displayed reminder of the vagaries of “official justice” it was feared as much as it was respected.

These claims did not go uncontested. Warlord armies and bandit groups also made use of the Dadao. However, it was the creation of numerous paramilitary groups and militias in the 1930s and 1940s that cemented the Dadao’s relationship with the modern Chinese martial arts and its place in the public imagination.

Martial arts instructors across China found that there was once again a practical demand for their services. The Dadao could be produced locally and was easily adopted by a large number of different fighting styles. In the hands of China’s martial artists this sword was transformed from an instrument of “official terror” to a symbol of community and personal empowerment. The public image of this weapon was democratized in ways that are hard to imagine. In fact, the images that these individuals created in the 1930s and the 1940s still effect how we think about the Chinese martial arts today. While this has only been a brief introduction to the social history of the Dadao, I hope that it will inspire some of you to go out and research the subject more thoroughly.